Marketing Effectiveness Lessons from the Pages of Fiction What Douglas Adams, Asimov, Pratchett, and Others Can Teach Us About Doing Marketing That Actually Works

Part 2: Winning the Right Game with Creativity and Effectiveness

In Part 1, I looked at how marketing effectiveness often goes wrong before it even starts by asking the wrong questions, chasing perfect but meaningless measurements, and mistaking activity for impact. From The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy to The Foundation, the lesson was clear: marketing, like life, is messy, probabilistic, and full of unknowns. The best marketers don’t fight that reality, they work with it.

But if Part 1 was about setting yourself up for success, Part 2 is about how to win and to win, you need both creativity and effectiveness working together. You can’t have one without the other. Like a Sudoku puzzle, you only find the right solution when every piece works in harmony. Creativity without effectiveness is just noise. Effectiveness without creativity is lifeless. Marketing needs both to cut through and to deliver.

That’s why I think of creativity and effectiveness as two critical components of strategy, not opposites. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned, especially from working in marketing effectiveness, it’s that experimentation sits at the heart of both. The best marketing isn’t a fixed plan. It’s an evolving strategy, shaped by testing, learning, and adapting.

It’s a lesson fiction understands better than most marketing textbooks. Terry Pratchett, Norman Lindsay, Frank Herbert — they all show what happens when you play the wrong game, and what it takes to win the right one.

5. Terry Pratchett – Night Watch: Don’t Win the Wrong Game (With a Little Help from Carrot)

In Night Watch and across the City Watch novels, Terry Pratchett gives us Corporal Carrot, a seemingly naïve but quietly formidable member of the Watch. In a city where corruption is accepted as normal, Carrot plays a completely different game. He believes in fairness, decency, and the rule of law and acts as if everyone else does too. He doesn't argue against the broken system he behaves as though it’s already fixed, and in doing so, he starts to change the system around him.

We can all learn a lot from Carrot. Too often, we end up playing someone else’s game, usually the one set by quarterly sales targets, performance dashboards, or media platforms pushing the latest shiny new metric. The result? Endless optimisation of things that don’t actually build brands.

The Marketing Trap: Optimising for the Wrong Metrics

I’ve seen countless brands focus their energy on chasing cheap clicks, squeezing down CPAs, or driving ever more impressions, all measurable, all immediate, and all largely meaningless if no one remembers the brand next week.

Take return on ad spend(ROAS). On paper, it looks like a sharp way to drive efficiency, but focusing on it often leads brands to hyper-targeted, narrow campaigns that speak only to people already about to buy. It can also encourage clever people to ignore fantastic data, if we spent a tenth of the time spent on optimising keywords on interrogating the strings of words around them imagine what brands could learn about consumers and their perceptions of the category. Rather than growing a brand; that’s picking off the easy wins and leaving long-term growth untouched.

A classic case of winning the wrong game.

The Alternative: Play for Brand Growth, Not Just Short-Term Wins

If Carrot teaches us anything, it’s that the real win comes when you refuse to play by broken rules and instead model a better way of doing things. In advertising, that means building Fame, Salience and Action, by meaningfully reaching as many potential buyers as possible, even if you can’t measure the impact immediately.

Look at brands like Specsavers, who’ve invested for years in distinctiveness and fame. “Should’ve gone to Specsavers” isn’t just a clever line; it’s a long-term investment in memory and mental availability, backed by consistent creative. But what makes Specsavers truly interesting is how they’ve evolved that fame, most recently with their ‘I Don’t Go’ campaign, which flipped their famous line on its head to reach brand rejectors.

Rather than playing the game of short-term targeting, Specsavers made a bold, fame-driving move that reached beyond immediate buyers and tackled a tough, long-term growth challenge: how to get people who actively reject the brand to reconsider. By highlighting their Home Visits service, designed for people who literally don’t go to Specsavers, they managed to reframe brand perceptions, shift consideration, and generate more than £19.8 million in incremental profit, all while deepening emotional connection and distinctiveness. With a very deserving IPA Gold that at MG we are really proud to have played a part in supporting.

The Takeaway for Marketers

If you’re playing a game, make sure it’s the right one. Don’t confuse short-term optimisation with long-term success.

Focus on brand growth, not just sales efficiency. You can’t optimise your way to fame.

Think like Corporal Carrot: behave like the system already works — and show what good looks like. If the metrics you’re being asked to hit won’t grow the brand, fight for better ones.

Pratchett understood that sometimes, you have to step outside the game everyone else is playing and start your own. The best marketers do the same. Imagine if more of us took Carrot’s approach, acting as if building brands for the long term, not chasing this quarter’s targets, is simply how the game is played. How much better would marketing be if we all played the right game, expected others to do the same and in doing so made it impossible for anyone to play it badly?

6. Norman Lindsay – The Magic Pudding: The Futility of Fighting Over What Never Runs Out

As a child, one of my favourite books was The Magic Pudding; for reasons I’m sure had nothing to do with the idea of an endless supply of delicious food. In Lindsay’s story, everyone is obsessed with owning the pudding, fighting, scheming, and chasing it day after day. But the irony is, the pudding never runs out. No matter how much they eat, there’s always more.

Marketing has its own magic pudding problem. Brands fight endlessly over the same small pool of short-term in market customers, relentlessly optimising CPA, tweaking bids, squeezing the last click as if that’s all there is to play for. They fight over slices of a pudding that, like in Lindsay’s story, could be limitless if they thought differently.

The Marketing Trap: Fighting Over the Same Shoppers, Endlessly

Its this mentality that leads us to burn through budget chasing the same "ready-to-buy" consumers over and over, fighting for a marginal sale today, instead of building brand fame that would create many more sales tomorrow.

It’s a fight for share of a static pie, when the real opportunity is to grow the market reaching people who aren’t yet in-market but could be, if only they knew and loved your brand. And when they do enter, to ensure it’s your brand that’s already lodged in their minds, like a beautifully memorable, never-ending herb-crusted venison and blackberry pudding.

The Alternative: Grow the Pie, Don’t Just Fight for Slices

Great marketing isn’t about fighting over the last crumb of the pudding. It’s about investing in brand-building that grows demand over time, making your brand famous, distinctive, and emotionally connected so that when people are ready to buy, they choose you.

Look at Guinness, John Lewis, or Cadbury, brands that have consistently invested in long-term distinctiveness, expanding the market in their favour instead of squabbling over today’s sale. It is our role as advertisers and marketeers to provide the evidence and business case required to bring the rest of the business along with us.

The Takeaway for Marketers

Stop fighting for crumbs. The biggest growth comes from future customers, not just today's shoppers.

Brand-building grows the pudding. Fame, salience, and distinctiveness make the whole market bigger and give you a bigger share.

Play the right game. Don’t exhaust yourself chasing what’s already there. Invest in creating what comes next.

Lindsay’s Magic Pudding is a brilliant reminder: if you’re fighting endlessly over something that could be infinite, maybe you’re playing the wrong game altogether.

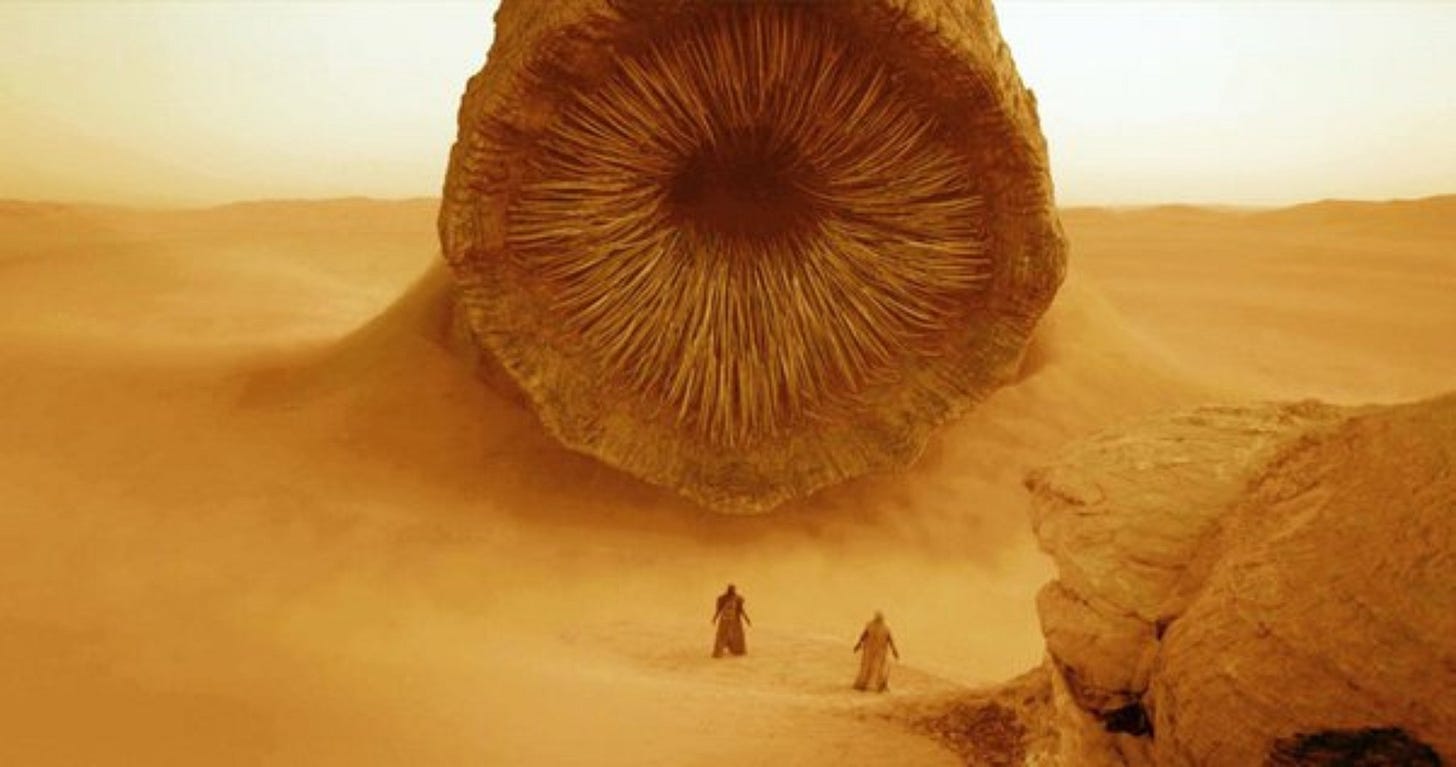

7. Frank Herbert – Dune: The Danger of Trying to Control Complex Systems

In Dune, Frank Herbert shows us what happens when people try to control complex systems and fail. Paul Atreides may have prescient visions of the future, but even he can’t predict all the consequences of his actions. The Bene Gesserit plot genetic destinies across generations, only to see their plans unravel. The desert ecosystem of Arrakis itself constantly resists human attempts to dominate it.

The lesson is clear: the more complex the system, the more dangerous it is to believe you can fully control it.

The Marketing Trap: The Illusion of Control

Marketers often fall into the same trap. With AI-driven personalisation, hyper-targeting, and vast data sets, we convince ourselves that we can steer every decision, shape every consumer journey, and dictate exactly how people should think about a brand. But markets are ecosystems, not machines. People don’t behave predictably, and culture evolves beyond anyone’s control.

I’ve seen brands pour energy into rigid segmentation, hyper-personalisation, and overly engineered brand guidelines, only to discover that consumers don’t play by those rules. A brand’s meaning is co-created, shaped by what people think, feel, and share not handed down like an instruction manual.

The Alternative: Build Systems that Bend, Not Break

Instead of chasing brittle control, great brands act more like gardeners than engineers. They nurture conditions for growth building broad mental availability, creating distinctive assets, and showing up consistently, but they accept that how people engage with the brand won’t always follow a plan.

This is where I like to think of Jonathan Haidt’s elephant and rider analogy. The rider (reason) thinks they’re in control, but it’s really the elephant (emotion, instinct, culture) that leads. The best marketing influences the elephant, creating emotional, memorable brand assets — rather than shouting instructions at the rider.

It’s also like designing a skyscraper that sways in the wind. Strong brands aren’t rigid; they adapt and flex with culture, but don’t fall over when something unexpected happens.

The Takeaway for Marketers

Stop trying to control everything. You can’t dictate every consumer thought, but you can be present, distinctive, and memorable.

Design for resilience, not perfection. Great brands know they’ll face unexpected moments, and they’re built to thrive in them.

Think ecosystems, not machines. Marketing is about creating the conditions for growth, not engineering every outcome.

Focus on broad reach and emotional connection. These are the tools that influence culture, not just short-term behaviour.

Embrace variance, don’t search for the perfect average. Markets are made of millions of unpredictable humans. Stop trying to compress them into a neat line on a graph. Real effectiveness comes from working with that diversity, not pretending it doesn’t exist.

Herbert’s lesson in Dune is simple but powerful: the tighter you try to grip a complex system, the more likely it is to slip through your fingers. Brands, like desert empires, grow best when they work with complexity, not against it.

Conclusion: Play the Right Game, and Play It Well

If there’s one thing these stories tell me, it’s that marketing isn’t about perfect control, clever shortcuts, or squeezing a bit more efficiency from the same old tactics. It’s about building brands that people care about brands that last. Not for the sake of being artistic, superior or achieving a higher purpose. But rather because its how you get closer to winning the game and selling more. Which is why we are all in this line of work.

That means marketers — and the agencies that support them — need to focus on the fundamentals:

Invest in creativity that people notice and remember, work that builds distinctive assets and emotional connections.

Make effectiveness the goal, not just efficiency. It’s not about how cheaply you can buy a click, but how well you can grow a brand that people think of first.

Experiment and adapt. Test what works, learn quickly, but don’t chase every shiny new thing without strategy.

Measure what matters. Focus on Fame, Salience and Action not vanity metrics that tell you nothing about future growth.

Build brands that can bend with culture. Brands need to be strong and clear in identity, but flexible enough to stay relevant as the world changes around them.

In the end, creativity and effectiveness are not trade-offs. They are the essential ingredients of strategy that works. The brands that win are the ones that understand this, and act on it — with confidence, clarity, and a long-term view.