This week, the latest edition of WARC’s Future of Measurement report landed. It’s sharp, substantial, and well worth your time full of smart thinking about how we understand marketing impact. I recommend it.

That said one slide, in particular, revealed far more than it intended. It makes complete statistical sense, but I’m not convinced it makes a strong marketing or advertising case.

It’s the hierarchy of experimentation slide, where RCTs sit proudly at the top, above geo-tests and ‘go-dark’ experiments. To be fair, the slide notes this hierarchy reflects scientific quality and validity. But even so, the implication is hard to miss: the more scientifically rigorous the method, the more valuable the insight.

The section goes on to feature solid case studies and the IPA’s MESI framework, all good and worthwhile in themselves. I have huge respect for the IPA’s work, and I’ve contributed to it myself.

But one idea keeps nagging: have we confused methodological strength with marketing relevance?

Why we advertise at all

Before I get to critique, let's restate what we are actually trying to do with advertising.

Good advertising drives business growth. Increasing the mix of products and services they can offer, the price they can charge and the volume they can sell.

It does this by building strong brands that:

Drive Fame: So more people know and understand the brand.

Build Salience: So more people think of it in buying situations.

Enable Action: So it's easier for more people to choose and buy.

That’s the job. Simple to say, fantastically hard to do.

Because achieving those outputs means influencing the behaviour of millions of people, most of whom aren’t thinking about you at all. Their decisions are messy, irrational, and shaped by a complex web of factors, many of which you’ll never be able, nor should want to be able, to track.

And it’s in that context that the whole ecosystem of marketing professionals deliver value, from strategic positioning and product development to advertising, branding and media to insight, research, technology, measurement, and analytics and many more. Each plays a role in shaping systems, not just serving segments.

Precision without perspective

I keep coming back to this slide because it reveals a deeper framing problem: we’re still obsessed with inputs, when we should be focused on outputs.

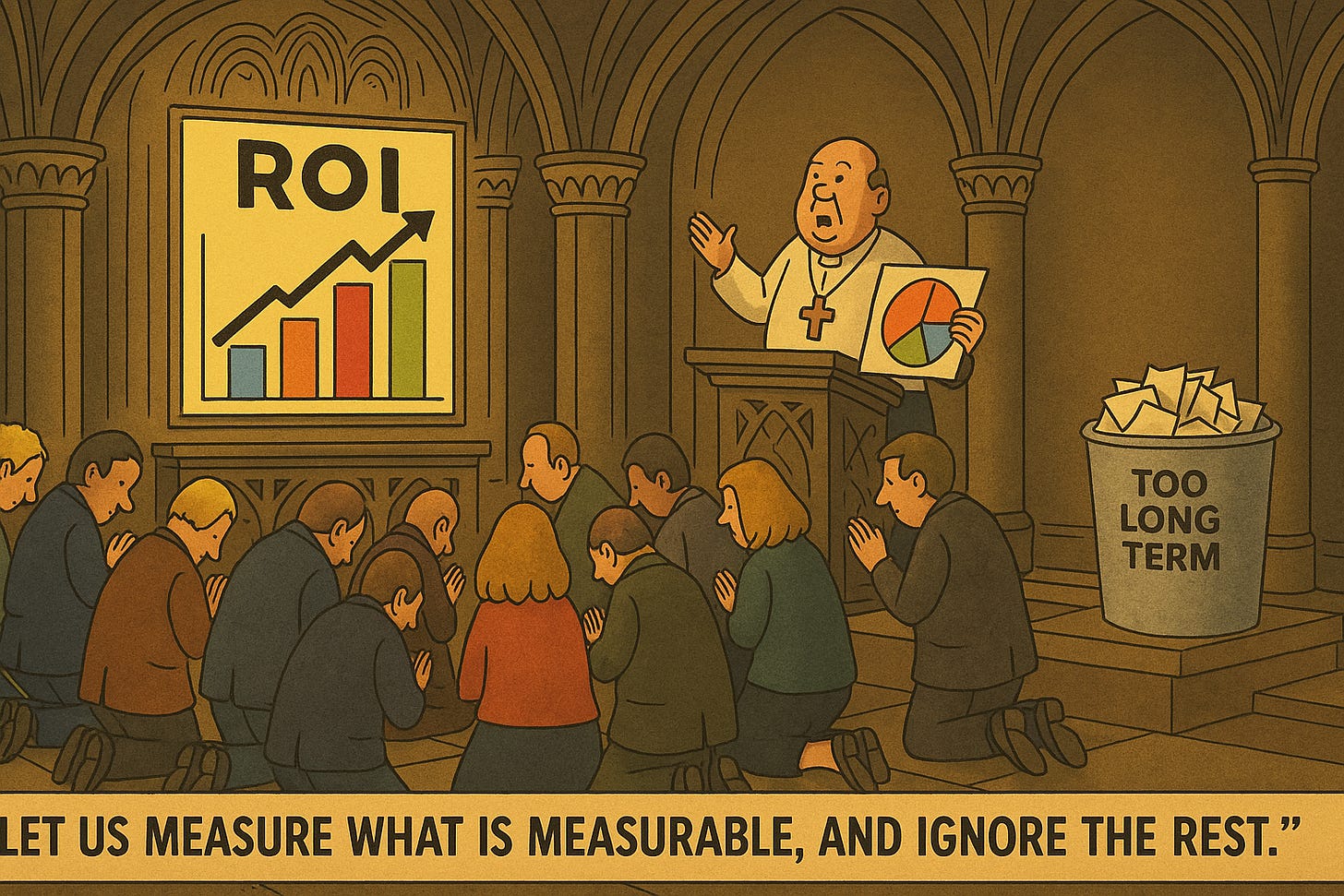

The rise of marketing experimentation has brought with it a gold rush of testing fervour. Once the preserve of academia or Silicon Valley, randomised control trials (RCTs) and geo-testing are now accessible to a far wider range of marketers. Finally, we’re told, we can isolate the causal effect of advertising. We can prove impact. "We can measure what matters".

But what if, in the pursuit of scientific precision, we’re missing the bigger picture? What if the narratives we celebrate most are optimised to measure the least important things?

This is not a rejection of rigour, its a rejection of reverence. It’s a call to remember what we’re trying to achieve. Advertising doesn't happen in test tubes. It happens in living rooms, bus queues and digital conversations. It works in systems, not silos. And too often, our most sophisticated methods are blind to the most important effects.

We’ve become experts at optimising what’s tidy and trackable and in doing so perfected the art of answering the wrong question

In search of significance

But as any good strategist will tell you, value depends on context.

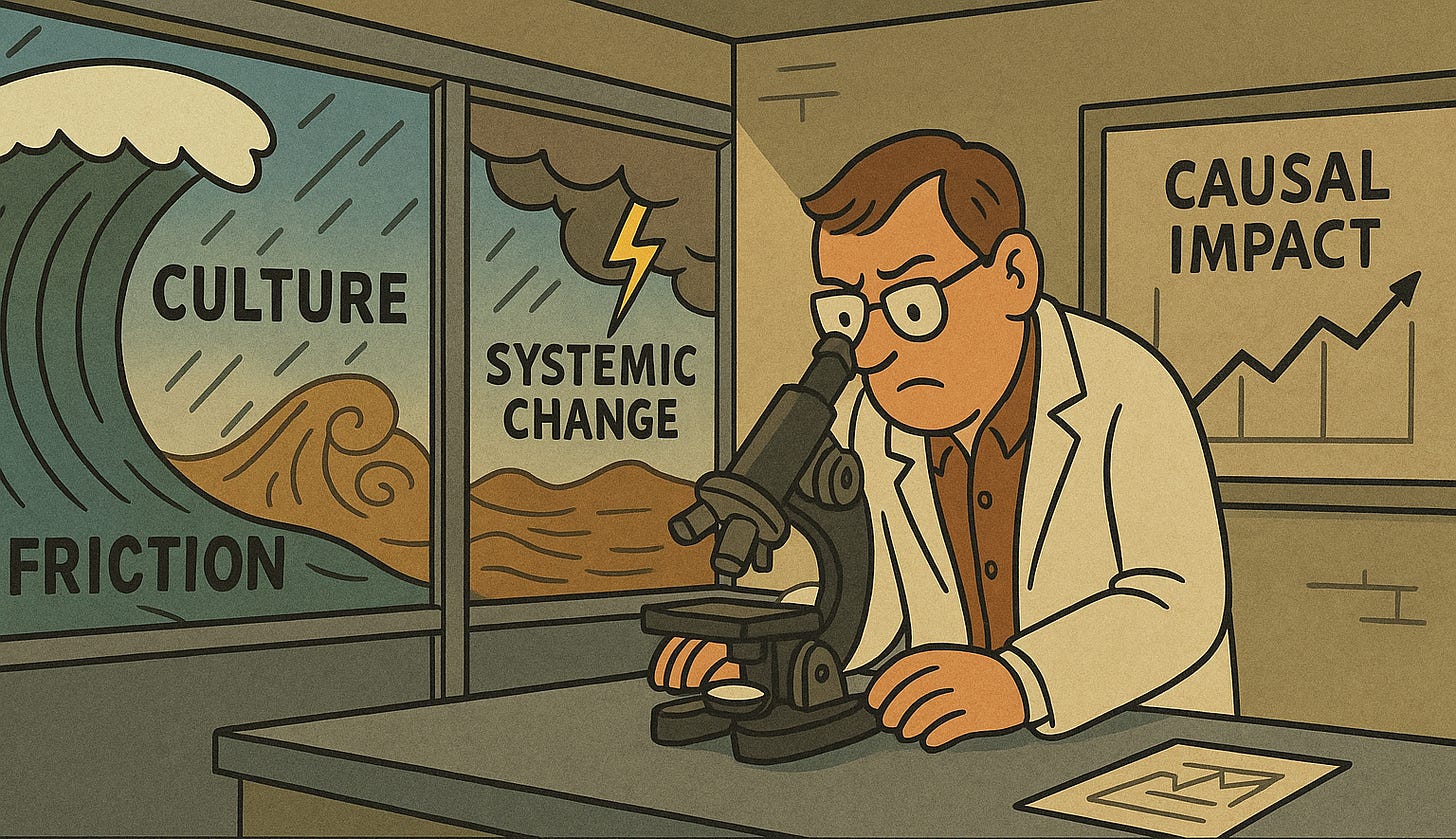

RCTs are excellent for detecting incremental impact on individuals who are already in-market. They are built for precision. But that very precision comes at a cost: they often miss the wider shifts that matter most. Cultural change. Normative shifts. The reduction of friction.

Take Sport England’s This Girl Can. The campaign wasn’t trying to push already-motivated women to attend one more class. It was designed to remove deep-rooted, systemic barriers that had kept millions of women from even entering the space. It wasn’t nudging the converted it was removing barriers to participation. Not efficiency, but empowerment.

Would an RCT have picked up that impact? If our tools cannot detect systemic change, perhaps we are not measuring advertising, rather admin.

This is the central flaw. We're measuring the ripple not the wave. The raindrop, not the storm.

The more we isolate variables, the less we see systems. The more we focus on individual response, the less we see collective improvements.

In our chase for what’s provable, we’ve stopped asking what’s meaningful.

That doesn’t mean we should give up on scientific rigour. On the contrary we need experiments that are both scientifically robust and designed to reflect the full complexity of real-world marketing goals. It’s not a choice between precision and relevance. The best experiments should help us make sense of complicated, systemic outputs not just clean, isolated inputs.

Partitioned truths, shared delusions

And the problem runs deeper. Because this measurement tunnel vision is mirrored in the way our teams are structured. Creative people make ads. Strategy people make plans. Measurement people tell us what worked. Rarely do those groups engage meaningfully with each other's disciplines.

This is a personal frustration of mine, and one I’ve encountered across brilliant teams in agencies, consultancies, and client-side roles. Too often, I’ve been told to "stay in my lane" or that the client team owns the relationship and I should just deliver what I'm told. And yes, there's always someone ready with the old 'colouring-in department' joke or a throwaway dig about 'marking your own homework'. We venerate collaboration, but too often it manifests as carefully managed partitioning. Each team curating their own slice of truth

We tell creatives to make something testable. We tell analysts to report, not imagine. We tell strategists to brief and back away. Then we wonder why our measurement doesn't shape culture or steer long-term brand building. So we get campaigns optimised for the chart, not the change.

Because only by combining disciplines do we unlock the ideas and the impact that matter. We need creative, strategic, and analytical voices all contributing across the process. Creatives, challenge what counts. Analysts, question assumptions. Strategists, push executions.

When everyone contributes to the whole system, we don’t just get better measurement we get more meaningful outcomes.

Ask better questions

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a criticism of the WARC report, which is thoughtful, well-constructed, and worth your time. My concern is how we, as an industry, tend to interpret and operationalise it. If anything, the report gives us the provocation we need to rethink the progress we’re making, and what outcomes we truly value.

Measurement should be an act of shared curiosity, not isolated validation.

So what does better look like?

It looks like a system that doesn’t just ask “what worked?” but “for whom, in what context, and against what barriers?”

It looks like multiple methods, layered insights, and simulation instead of simplistic attribution. It accepts that not everything valuable can be proven in the short term and that chasing certainty too often means sacrificing meaning.

Analytics is welcome essential, even. But science without strategy is sterile. And measurement that forgets marketing’s purpose? That becomes precise about the irrelevant.

We don't suffer from a lack of data, too often it's a lack of nerve.

We owe it to our discipline to ask better questions. Together.