We are getting creativity wrong

And that misunderstanding is costing us influence, integration, and impact.

Let’s start with a simple truth: creativity is not a department. It’s not a mood board, or a pitch theatre. It’s not a personality type, or a job title. Creativity is seeing a problem differently and solving it in a way that works.

But in much of our industry, we’ve come to treat creativity as synonymous with creative quality the brilliance of the final execution. That’s a mistake. Creative quality matters enormously, but it’s the output of creativity, not the definition of it. When we collapse the two, we narrow what we value, who we include, and how we prove our worth.

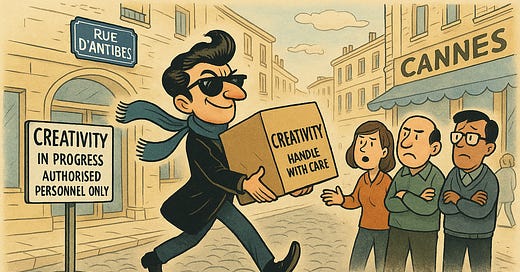

Somewhere between the brainstorm and the awards show, advertising lost that distinction. “Creativity” became shorthand for the cleverness of the ad, as if originality only counts once it’s wrapped in a 30-second film or hung on a billboard.

It flatters a few, excludes many, and weakens all. Because when we reduce creativity to execution, we shrink its power. from a shared commercial capability to a performance art.

And this isn’t just a theoretical concern. I’ve experienced it firsthand.

I’ve been excluded from client conversations because my title contained the word “analytics.” And I’ve seen it happen to others: brilliant strategists, analysts, media thinkers quietly told that creativity isn’t their job. That their role is to observe, not originate. And when they do originate, when they bring fresh ideas in their own fields, it’s not recognised as creativity at all. It’s dismissed as mechanics. As engineering. As something useful, but not imaginative.

It’s a loss. Not just of voices, but of value.

We all love to talk about collaboration, but our creativity narrative risks building silos of ownership. We talk about inclusion, but risk rewarding only one style of thought, confident, charismatic, creative with a capital C. Meanwhile, others are quietly disqualified because their creativity doesn’t wear sequins or come with a TED talk attached.

Events like Cannes are billed as the pinnacle of creative celebration. But in format, they often resemble an extrovert’s endurance test: constant interaction, high-polish performance, and visibility as value. I know brilliant minds who feel they should go to be seen, to be connected, but quietly dread the experience. Not because they lack creative worth, but because the event itself is built for a narrow type of presence. That’s not a moral failing. It’s a design flaw. And it mirrors the same problem we face inside our companies: we reward one mode of contribution, while marginalising others. The result is the same, brilliance goes unrecognised, and the definition of creativity shrinks yet again.

If we want to broaden the work, we need to broaden the stage. Because when we only hear from those comfortable with the creativity status quo, we don’t just exclude individuals. We narrow the entire field of vision. For the introvert, it’s less a festival of creativity and more a networking pentathlon in the sun.

This is where our own industry habits work against us. Even in well-intentioned work, the confusion creeps in. Take System1’s excellent The Creative Dividend. It offers clear, data-backed proof of how better creative quality drives commercial impact. It’s rigorous and valuable. But it also uses “creativity” and “creative quality” interchangeably, as though the concept and the output are the same thing.

They’re not. And if there’s one industry that should understand the power of language, it’s ours.

This is where precision matters. There’s a meaningful difference between someone who thinks creatively, someone who reframes problems, connects dots, proposes a new approach and someone who is a creator. The latter makes something: a film, a script, an image, an experience. Creating artefacts from scratch requires more than just novel thinking, it takes craft, discipline, and often years of refinement. That’s why great agency creatives are so valuable. But to say only those who produce are “creative” is like saying only composers understand music. It’s both false and self-defeating.

Creative quality in advertising is crucial. But creativity itself is broader. It’s not just in what you make, it’s in how you think. In how you solve. In how you shape strategy, shift perception, structure a plan or spot an opportunity no one else has seen.

We need to stop thinking of creativity as a rare spark and start treating it as a system. One that spans functions. That demands rigour as much as flair. That lives not just in the final frame, but in every commercial decision along the way.

Because when we teach creativity, we scale it. When we scale it, we embed it. And when we embed it, we finally give ourselves the evidence to defend it.

Creativity isn’t magic. It’s a discipline.

And it’s time we started treating it like one.

So:

If you think creativity only happens in the ad, you’ve missed where the value lives.

If you think only “creatives” own it, you’ve built a church when we need a commons.

If you think creativity can’t be taught, you’re mistaking mystique for maturity.

And if we keep presenting creativity as something separate, something indulgent, ornamental, disconnected from business value… then don’t be surprised when it’s the first thing cut.

Because properly understood, creativity isn’t indulgent. It’s growth infrastructure.

Not a mood, but a method. Not an indulgence, but an investment.

If that sounds unromantic, good. Romance never balanced a budget.